Reading aloud to my teenage sons will cost me

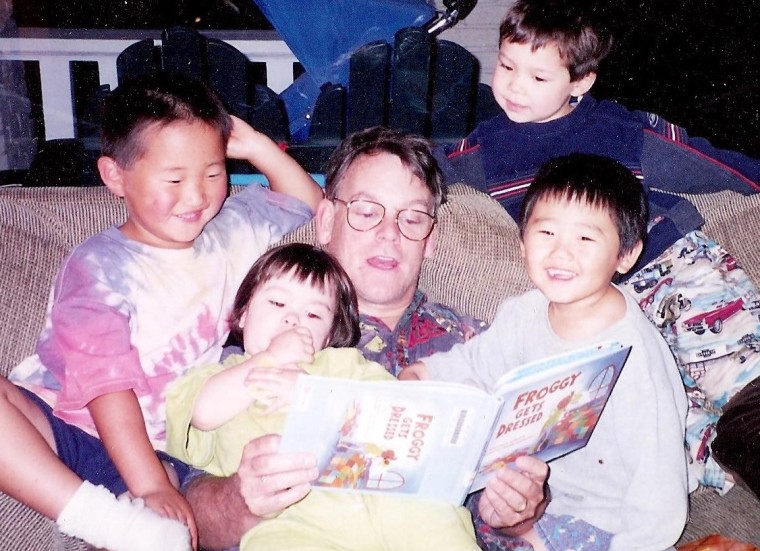

In happier times, my husband, Mark Funk, reading to (L to R) Casey Funk, India Bock, Pierce Bock and Charlie Funk

My boys used to love books and stories. I would read to them in the evenings before bed or in the car on long road trips, or sometimes out on the front porch when the sun was just right — not too hot or glaring.

I read them all my childhood favorites as well new classics, including all seven Harry Potter books and Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson series.

Of course I hoped that sharing my love of reading and language would instill in them the same. But mostly I read to them because it was fun, effortless bonding, and they seemed to need and enjoy it as much as I did.

Then they became teenagers.

When my older son, Casey, decided he no longer liked being read to, we were into the third fat book of Christopher Paolini’s Inheritance Cycle, which I thought was lot to invest in a story without the payoff of an ending.

Charlie, my youngest, stopped letting me read to him half way through Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games series. He’d just go see the movie, he said, as if that were the same thing.

After that, my offers to read got about the same response as my telling them to clean their rooms. They didn’t even want me in their rooms, let alone sitting on or by their beds. It was like I had mother germs.

I mourned the loss. In the evenings, I’d pace the house, restless, looking longingly at my favorite cozy spot on the love seat next to the fireplace, the abandoned book-in-progress on the end table.

“Are you sure I can’t just read a few pages?” I’d plead.

“No, Mom. Can you leave me alone?”

I knew not to take it personally. They were starting the separation process on the road to adulthood. I understood that. What I didn’t understand was their abandonment of books and reading altogether (unless it was absolutely required by their teachers). I thought all those hours of reading to them would plant the desire to read on their own. It didn’t.

“I hate reading,” they tell me now. Hate is a strong word meant to push my book-loving button, but knowing that doesn’t make their protestations any easier to take.

I hold out hope they’ll come around. They’re still drawn to narratives, just not from books. Most of their attention and free-time is now sucked up by screens — movie, television, computer and cellphone – playing games, watching Netflix, seeing the new Star Wars movie, or reading and composing the shorthand text and Skype messages that substitute for human conversation.

The other day, I quizzed Charlie, now 16, and his friend about reading. (They put up with it because I was buying them lunch.)

What did they like to read? The friend had read Jurassic Park a while back and enjoyed it more than the movie. Okay, there’s hope, I thought, until Charlie reminded me that he hates to read.

I persisted. Did they have friends who liked to read? No, not really. Okay, maybe a couple of girls they knew, but no guys.

Why? Because boys would rather play sports or watch Netflix, and the “nerdy boys” would rather play video games. Charlie said he would rather sleep.

When I pointed out to him that his dad is a male person who loves to read, he said, “Yeah, but he’s old.”

Finally I stopped torturing them and let them finish their food.

As a writer about to send a young-adult novel – my first – into the world, I could choose to be depressed by this conversation. But I refuse to believe it’s as bleak as my son and his friend make it out to be.

The world is full of readers, and they’re not all girls and senior citizens. Which leads me to consider something so bold some might say it’s crazy.

Many a successful writer, including Steven King, has said that you really should read your work aloud to hear the draggy, clunky bits.

That gave me an idea. If I have to read my 85,000-word novel aloud, I may as well read it to someone, preferably a young adult, maybe even a couple of young adults, who would give me feedback on what worked and what didn’t.

Now, I know that the two young adults I have in mind would need some incentive, say, in the form of a large bribe. They’ve already flatly refused to read my draft on their own.

“Maybe after it’s published,” is Casey’s stock answer.

“That won’t help me,” is my stock reply.

So, after much negotiation, he and I finally settled on price: $200, half of which is to be paid up front. Charlie, of course, wants the same amount, but in cash (no bank transfers for him).

Will they be honest in their feedback if I pay for it? Yes, I believe they will. They’ve never tried to spare my feelings.

My best writer friend thinks I’m nuts, and I only told her about the reading aloud part, not about my reluctant audience.

In my place, would you pay your kids to read to them? In my sons’ place, would you take the deal?

Feel free to chime in, even if you agree with my friend that I am indeed insane.

In my next blog post, I’ll report back on what went down . . . if I’m not crying in my pillow.