MAYDAY: An international radio distress signal used by ships and aircraft

Chapter 1

August smells of fish and creosote, sun-warmed and oily. People wrinkle their noses at the stink, but I like it. It’s the smell of boats returning. I’ve got my lucky Minnie Mouse beach towel, a can of Diet Pepsi, and my transistor radio. I’ve got the binder I started when I was six with “Homecomings” written on the cover inside a border of blue stars. Nine years. Nine fishing seasons in Alaska. Trollers in one column, purse seiners in another, writing in my best cursive all their clever, sentimental names, even though the only one I really care about is the Lady Rose, the beautiful red troller Dad named after me.

The west end of the Port Dock offers me a clear view of the channel. I kick off my flip-flops, spread my towel over the bull rail, and sit straddling it, my right leg dangling over the water. It’s early, but the families have already started to gather. There’s Mrs. Baldwin in her wheelchair being pushed by her grandson. And Mrs. Thompson, who usually spots the first fishing boats through the binoculars she keeps on her windowsill. The pregnant clerk at Tradewell is here with her little boy. And there’s my old Sunday school teacher, Mrs. Ward, with her daughter-in-law. Some kids are playing tag. I’m not sure who they belong to.

Mrs. Ward waves hello and walks over, casting me in her ample shade. She cradles a big bunch of flowers—carnations, I think. Should I warn her that flowers are bad luck? Or maybe that’s just flowers in the water. She’s probably okay.

“Is your father coming in today?” she asks.

“No, not yet. Maybe this weekend.”

“Bet you’re counting the minutes.” My grin must give me away because she laughs. “How’s your mother doing? I haven’t seen her in a while.”

My mother is probably still in her bathrobe, but I don’t tell her that. “She’s fine . . . ready for the season to be over.”

Mrs. Ward cups her mouth with her free hand and leans in as if to tell me a secret. “The only thing harder than living with a fisherman is living without him.”

I giggle at that. “Pretty flowers,” I tell her, but her attention has shifted to Mrs. Thompson, who comes over to chat. The two women walk off together and I’m free to switch on my radio. Before I do, though, I make up a test. If the first song I hear is happy, I’ll see Dad this week. If it’s sad, it’ll be longer. From Ketchikan, Alaska, to Annisport, Washington is three to five days, including fuel stops. Dad called Tuesday night, and today is Thursday, so he’ll probably get in this weekend. Tonight he’s supposed to call again and tell us where he is.

I turn my radio on and get what I think is a song, until I hear Things go better with Coca-Cola. Damn. I hate it when they fool you. I have to wait through advertisements for Doublemint Gum and Rice-A-Roni and finally a station-identification before I hear a familiar big-band intro and the Beatles singing, “Love, love, love.” Nine loves. I’ve counted. I close my eyes and sing along, trying to send Dad all the love I can. Then I pop open my Pepsi—take that, Coca-Cola!—and turn to a fresh page in my notebook. At the top, I write August 17, 1967.

I look up just in time to see Mrs. Ward and Mrs. Thompson taking turns glancing back at me—this plump and desperate girl who obviously has nothing better to do with her last precious days of summer. What they don’t know is that summer is purgatory when you’re an only child stuck with a moody mom. Talk about desperate. The year I was born, she spiked Dad’s dinner with powdered milk because she’d had a “death dream” about him. He got so sick he had to postpone his departure for Alaska by a whole week. I don’t know how my grandparents found out. Maybe Mom felt so bad she confessed. But they weren’t sympathetic at all.

Thank heaven I came along because I brought everyone together in a way that only a baby can. Now Grandpa Bill and my uncles laugh about the “Lac Attack,” though Grandma still hasn’t completely forgiven my mother. That’s according to my cousin, Dena, who knows everything.

I flip back to the first page in my notebook. GRACE, the purse seiner my uncles named after my grandma, is written in big, blocky letters on the back of the grocery receipt Mom gave me out of her purse. The scrap is starting to lift away from the notebook paper I pasted it on. I press it down and turn the page, reading back through boats named for luck and strength and ladies.

Logging the names started as a way to kill time while I waited for Dad. Now it feels like an important ritual, a reverse blessing of the fleet. Dad understands. He’s the one who taught me all the nautical sayings and superstitions, including the “red sky” saying everyone knows. “Never leave port on a Friday.” That’s another one. And women are bad luck unless they’re gracing the bow as a figurehead. A boat is always a she, never a he, because captains love their ships more than the sweethearts they leave behind. Dad denies feeling that way about the Lady Rose, but I have to wonder when he seems so excited to get going each spring.

He says naming the boat after me is an honor. Mom says it’s yet another example of guilt talking because he’s away so long. Either way, I feel an almost human love for the Lady Rose and all the other lady boats, with their pretty names:

He says naming the boat after me is an honor. Mom says it’s yet another example of guilt talking because he’s away so long. Either way, I feel an almost human love for the Lady Rose and all the other lady boats, with their pretty names:

Miss Sharon

Lizzy Mae

Ma Cherie

Little Queen

Rebecca

I’m not sure why Dad chose my middle name instead of my first. I guess Rose sounded better to him than Ida, which is Mom’s favorite girl name. She says she got to name me because Dad saddled us with the last name Petrovich, which in Croatian means “son of Peter.” I don’t know if there’s a surname ending for “daughter of.” I’ll have to remember to ask Dad about that when he gets home.

The channel sparkles with little waves that turn into a thin band of light at the horizon. Past where I can see, the water widens into Rosario Strait, which connects to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which then leads to a rugged and stormy stretch of Northwest coastline known as the Graveyard of the Pacific. Dad won’t be out there. He’ll be on the protected east side of Vancouver Island, coming home early so we have some summer together before I start high school. The purse seine fishermen, including my Uncle Alex, are still up in Alaska, scooping up the salmon that are returning to the rivers to spawn.

“Easy over-fishing,” Dad calls it, which always makes me think of eggs. If my uncles are over easy, Dad’s scrambled, because he fishes out in the open ocean, where the weather and waves toss him around like a cork. It’s dangerous out there, but the payoff, he says, is a hold full of the most beautiful fish you ever saw. He’s shown me pictures of kings, the biggest and most prized salmon. He once caught and lost a fish that he said weighed well over a hundred pounds, more than I did at the time.

“Now your spring salmon has a choice,” he’ll say. “He can bite on your line or not. The purse seine fishing your uncles do is different. They circle a net around a run of homebound salmon and trap them. The poor things get all bruised and battered thrashing against each other in the net. That’s no way to treat a fish.”

He’ll go on and on about the virtues of trolling versus net fishing even though it’s a lost cause. All Slav fishermen are purse seiners and proud of it. How did that Thanksgiving argument start? I don’t remember, but Dad must have had just enough dandelion wine to accuse all net fishermen, including my uncles, of being too greedy. “We have families to support, not to mention get back to,” Uncle Pat shot back. He accused Dad of “playing cowboy” with his own life, which made Dad so mad he slammed his fist on the table, spilling his wine.

The wind shifts and I’m hit by a strong, spicy smell. Tabu. The only perfume I know that can compete with fish and win, which is probably why Mom wears it.

“I thought I’d find you here.”

I turn to find her standing behind me. She’s all dolled up—navy blue dress, gold pin in the shape of a clam shell, and bright red lips that bring out the strawberry-blond curls peeking out from the edges of her white chiffon scarf. Most of the other women here are wearing housedresses or pants with simple tops. Except for the scarf around her head, Mom could be working the perfume counter at Frederick & Nelson. And that can only mean one thing.

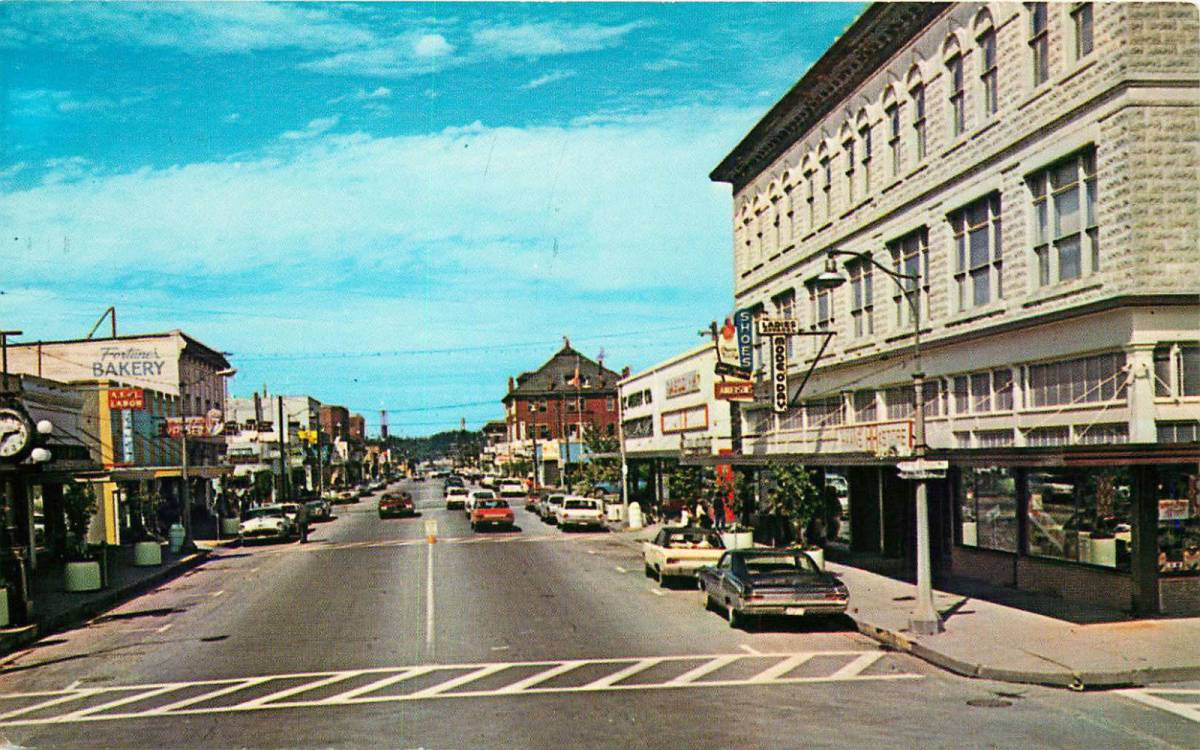

Anacortes (inspiration for “Annisport”) in the 1960s

Anacortes (inspiration for “Annisport”) in the 1960s